|

The Soil Carbon Challenge Today we understand as never before the crucial role that carbon-rich soil organic matter plays in the quantity and quality of the food we grow, in moderating flooding and drought, in the quantity and quality of runoff and groundwater, in biodiversity, and in the composition of the atmosphere, especially its carbon content. However, our institutions and political systems have been largely unable to take advantage of the great opportunity this understanding offers, because like most of us they focus on problem-solving, on managing against threats. For example, since 1900 the U.S. Department of Agriculture has been managing against food contamination, low prices for agricultural commodities, soil erosion, hunger and malnutrition, fire in the forests, nitrate pollution, and on and on. The #1 recommendation to land managers of its small Soil Quality Team is to enhance soil organic matter, yet the overall effect of USDA policies, by fostering tillage, fire, and chemical use, is to oxidize large tonnages of soil carbon into the atmosphere, and limit its replenishment. Climate policy proposals are even more tightly focused on problem-solving, on threats and risks. Because of the great size of the soil carbon pool compared to atmosphere and vegetation, and the magnitude of its responses to human decisions, the soil carbon factor threatens to reframe the climate debate, discomfiting both climate activists and agribusiness, and increasing the uncertainties all around. Proposals to commodify soil carbon as a potential "offset" to fossil fuel emissions have raised resistance from every sector and stripe, yet such proposals have framed almost all of the recent research on soil carbon. If you want to find out how fast a human can run 100 meters, do you build a computer model, do a literature search, or convene a panel of experts on human physiology to make a prediction? No, you run a race. Or many of them. There’s been tons of talk about soil carbon, but it’s time for motion: to show with good data what’s possible, and recognize those land managers who know how to increase soil carbon. Where things are stuck or the way forward is unclear, a competition can supply creative and unconventional solutions. A competition can leapfrog the decades-long cycle of research, pilot projects, legislation, and incentives, and can showcase leadership based on knowhow and performance rather than on promises and predictions. A competition can tell the stories of soil carbon to citizens, governments, and farmers better than anything else. Competitions change the question from Can it be done? to How well, and how fast? The Soil Carbon Challenge measures soil carbon change with permanent plots, field sampling, and dry combustion tests. Three baseline plots make an entry, resampled at years 3, 6, and 10. It’s not an offset scheme. It’s the next agricultural revolution, and you can bring it to your district, sector, or community. |

We're proud to report that Tony and Andrea Malmberg, of Union, Oregon, experienced ranchers and holistic planned graziers, are the first entrants in the Soil Carbon Challenge.

The Soil Carbon Challenge is an international as well as local competition to see how fast land managers can turn atmospheric carbon into soil organic matter, and recognize those who do (see sidebar).

When. The first two carbon plots were established and sampled on August 16, 2010, and the third was established and sampled on September 24, 2010.

Where. North and east of Elgin, Oregon, the Malmbergs' property consists of gently sloping grasslands with some patches of timber. Elevation is about 3600 feet (1100 meters) above sea level and average precipitation is about 15-20 inches (380-500 mm) annually. The predominant soil is a mollisol, Lookingglass silt loam.

|

| Tony Malmberg during soil sampling on CRP ground. |

For these experienced ranchers and graziers, establishing baseline monitoring was a natural first step with their recently purchased property. For the function of the ecosystem processes at the soil surface, they chose the Land EKG method developed by Charley Orchard (http://landekg.com). "Land EKG provides the diagnostic test to know where we best focus our tune-up to get the ecosystem engine humming," says Tony.

"The carbon data tells us how much horsepower we’ve got under the hood, or under the soil surface in this case."

Soil carbon is a basic indicator of ecosystem function, water retention, and productivity. We used the Soil Carbon Coalition's plot specifications to co-locate permanent plots with the Land EKG transects that Charley Orchard set up and read.

"Acknowledging diverse social values, and meeting increasing demands for enhancing water cycling and carbon cycling can be important in marketing our grass fed beef," notes Tony. He regards both Land EKG and the monitoring of soil carbon change provided by the Soil Carbon Challenge to be important to his success.

|

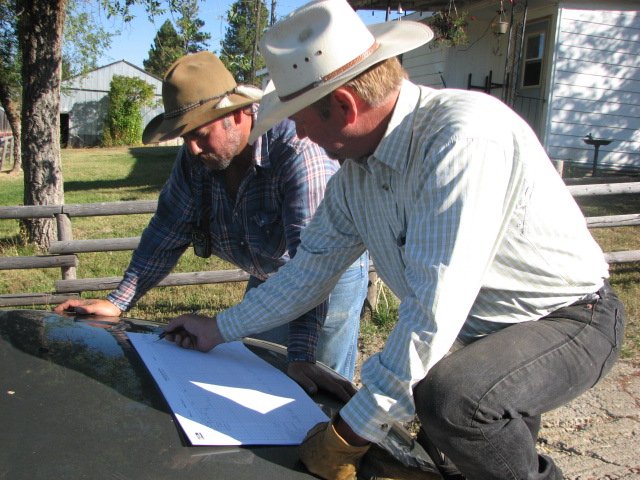

| John Cheever and Tony Malmberg consult the grazing plan prior to turning in cattle 23 years after the property was enrolled in the Conservation Reserve Program |

One of the ways Tony hopes to engage with policy is by creating an example of a successful transition away from the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), in terms of land health, community health, and economics. The property, which the Malmbergs recently purchased, has long been used for grazing, and for wheat farming. In 1987, several hundred acres of the farm ground were enrolled in the new CRP, and seeded to perennial grasses. A continuation of the Soil Bank programs of the 1950s, CRP was intended to take highly erodible cropland out of production by paying for the establishment of permanent cover and then paying annual rent to the landowner. Grazing was prohibited, although recent rule changes have allowed some exceptions. Currently about 31 million acres nationwide are enrolled in CRP, an area half the size of Wyoming. In 2009 the program cost $1.867 billion, or about $60 an acre per year. U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack said that "the CRP is the largest carbon sequestration program in the country."

But many criticize the program for hurting the economies of rural communities and increasing dependence on government programs, while only doing a mediocre job of enhancing ecosystem health, biodiversity, and soil carbon. The Land EKG transects on the 23-year rested grasslands show the water cycle functioning fairly well, in that the soil is well covered with litter, and there were no signs of soil movement, but that energy flow, community dynamics, and mineral cycling were significantly under potential.

Charley Orchard's monitoring report for one site includes the following:

"Three of four impaired processes (all but water cycling) are common results of CRP practices."

"Allow energy flow to occur. . . . Using grazing (as high stock density as possible) with initially heavy stocking rate followed with appropriate rest period and again grazed (not as heavy) will stimulate system and desirable plants."

The CRP did generally accomplish its objectives, which were to reduce erosion and take cropland out of production. But the Malmbergs have a vision, a holistic goal, that goes beyond objectives, to the function and condition of the ecosystem processes, to the health of the rural community they live in, and to their own quality of life. To move toward that, they need to enhance the ecosystem processes, using both the Land EKG and soil carbon monitoring as a guide, and to use tools which the CRP forbids, such as planned grazing and animal impact.

|

| Planned grazing starts, October 1, 2010 |

What. Because soil carbon plots have only recently been established and sampled, there is no change data yet. The plots will be resampled in 2013, though the Land EKG transects will be read every year.

Here are the results from the first two carbon plots:

Rawhide pasture plot: (not in CRP, used for grazing until grass/water ran out):

0-10 cm layer: 2.48 % carbon, bulk density 1.05 10-30 cm layer: 1.91 % carbon, bulk density 1.20

Woods pasture plot (CRP for 23 years):

0-10 cm layer: 2.62 % carbon, bulk density 1.17 10-30 cm layer: 2.07 % carbon, bulk density 1.14

Recent Posts

Archive

Categories

- Events (2)

- policy and framing (23)

- ruminations (3)

Tags

- atlas (2)

Authors

- Peter Donovan (137)

- Didi Pershouse (3)